Did you know that the discovery of tea happened by fluke? That and other fascinating stories of the beverage

According to a popular Chinese legend, the discovery of tea was almost accidental. In 2737 BC, when Emperor Shennong was drinking boiled water few leaves from a nearby tree blew into his bowl, changing the water’s colour and taste. The emperor took a sip and was pleasantly surprised by its flavour and restorative properties. Thus was discovered tea.

Back in India, the mass commercialization of this morning drink was possibly the result of Britain’s love for tea. The country’s tryst with tea began with their queen in the year 1662. Catherine of Braganza, originally from Portuguese, loved her tea and gave the drink her royal stamp of approval. This led to the East India Company placing an order for 100 pounds of China tea in 1664.

From then on, the British continued to trade tea with the Chinese, giving them silver in return for tea at first, but due to silver shortage in England, they started smuggling opium from India to China. For opium, China paid in silver, which was then used to purchase tea. However, in the second half of the 18th Century, due to the Chinese efforts to halt opium trade as well as the end of the East India Company’s monopoly on trade with China in 1834, the British started to look for other source markets.

Robert Bruce in 1823 discovered the tea plants, Camellia sinensis growing wild in upper Brahmaputra Valley, Assam, but the leaves were not being consciously used to drink tea in the country. Only the native tribes of the region, the Singphos and Khamtis were acquainted with the bush, and drank a brew of its leaves. The government of Assam’s records show one of the first tea gardens was established in 1833 in erstwhile Lakhimpur district, and by 1855 tea cultivation in the state amounted to over half a million pounds. The British also used samples taken privately from China, and planted them in the high elevation regions of Darjeeling and Kangra. In 1847, the first official tea plant nursery was established in Darjeeling. Darjeeling black tea, one of the best in the world, evolved from the original saplings from China.

Photo Courtesy: Simon / Pixabay

Although we had a lot of tea being grown in the country, Indians were quite wary of the beverage at first. Mahatma Gandhi wrote a chapter in his book, A Key to Health, explaining that tannin, the compound that gives tea its astringency, was bad for human consumption. To combat this stigma, in 1903, the British government established a unit that extolled its virtues, called the Tea Cess Committee. They started putting out illustrated advertisements at railway stations with instructions for brewing tea and cliams about the drink’s benefits. The Indian style of making tea, aka boiling the leaves, was popularised in the 1930s and 40s, when vehicles travelled through the urban and semi-urban areas of Bengal, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra explaining how to brew tea. It is said that boiling was encouraged as an antidote to get rid of the supposed ‘bad’ things in tea, and it is still how the beverage is mostly made in India. The efforts of tea brands like Brooke Bond and the erstwhile Tea Board led to a rise in consumption in the 1930s.

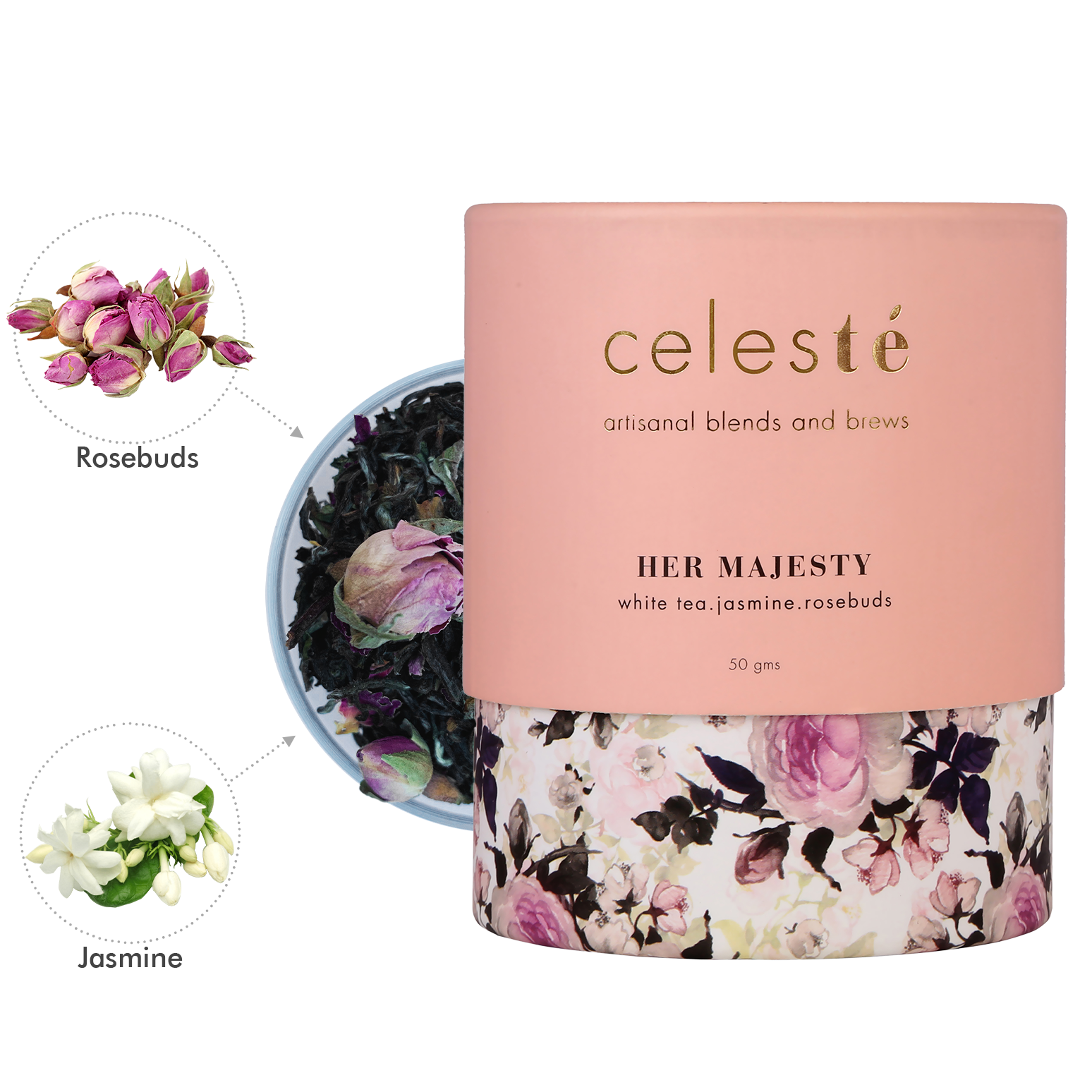

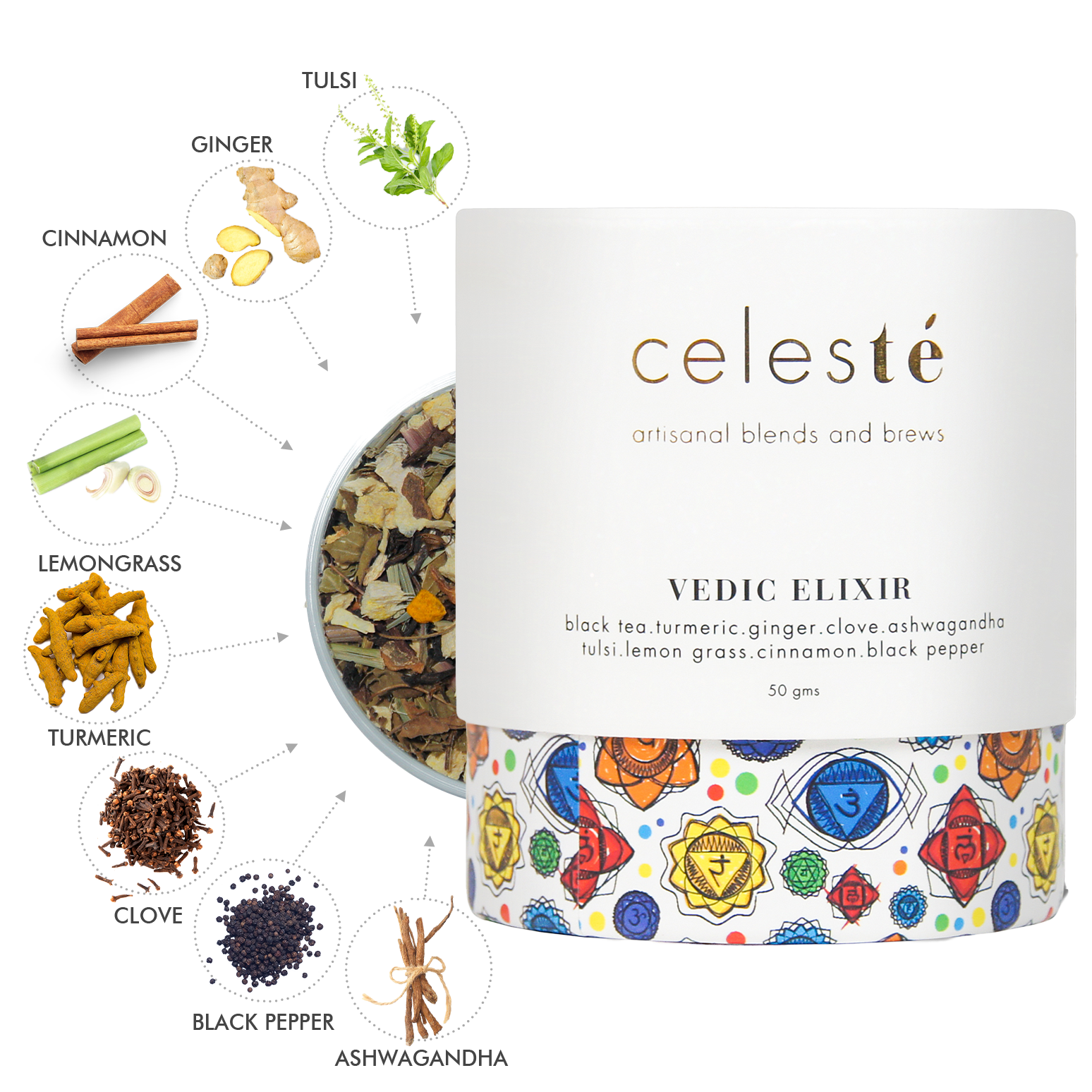

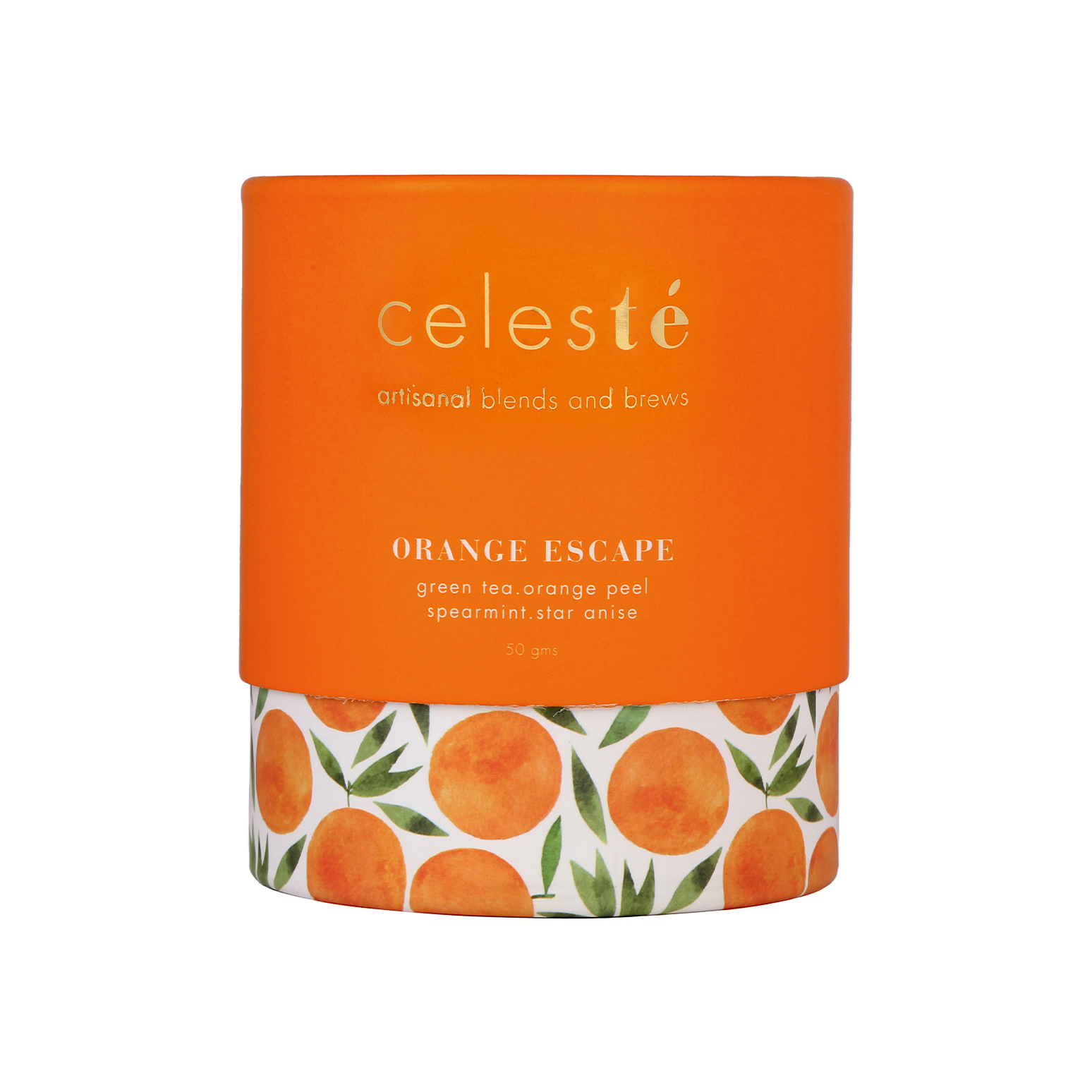

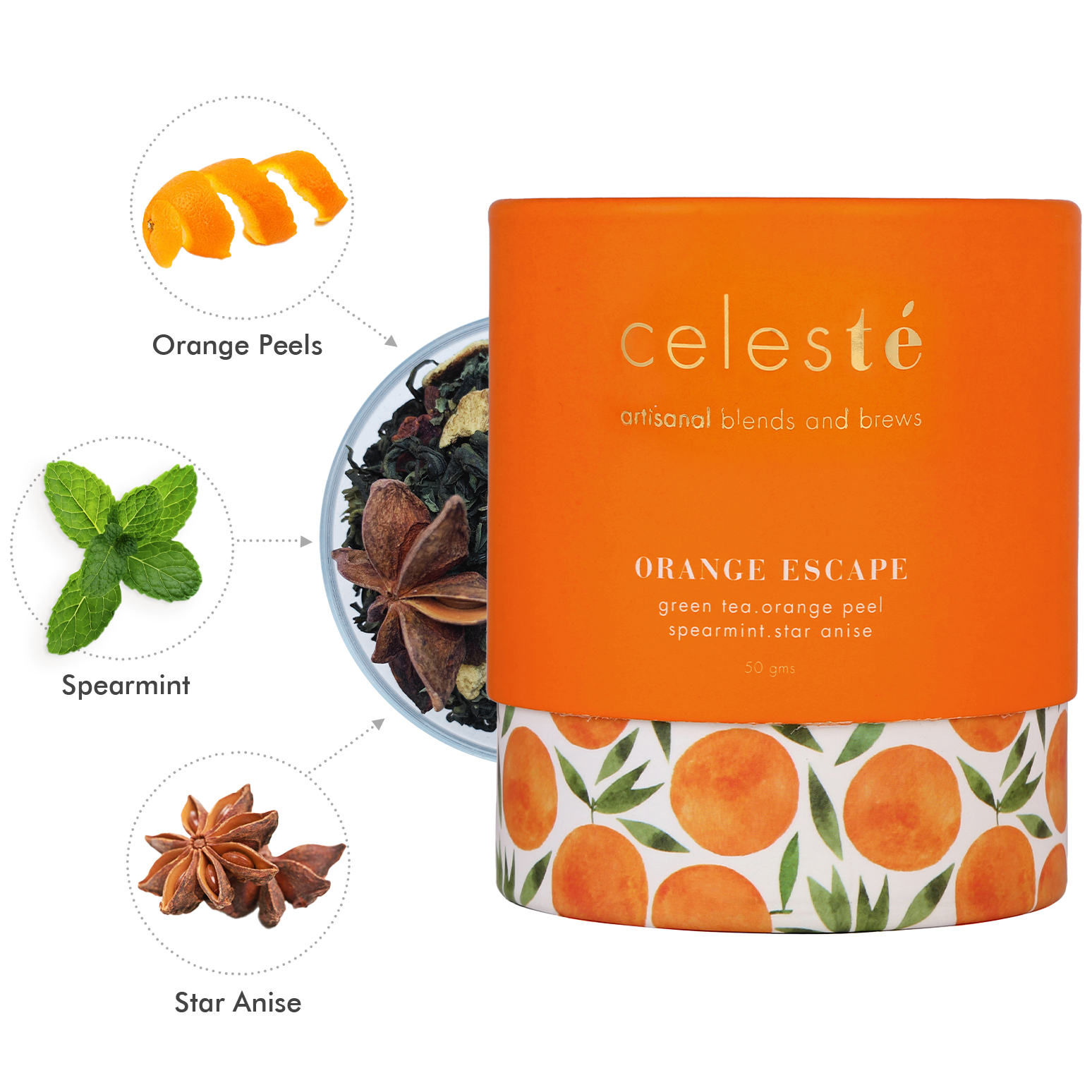

Now, almost 85% of total households consume tea, and in 2020, India produced 1255.60 million kilograms of tea. Unfortunately, though, according to Anubha Jhawar, founder of Celesté, a luxury tea brand, consumers are still not getting the best of what the country is growing, the top quality teas are mostly exported.

Photo Courtesy: Harsh Pandey / Unsplash

“In Bengal, Calcutta, Darjeeling, Kalimpong, people still maintain the tradition of tea along the lines of how the British used to drink it, no milk, no sugar,” says Jhawar. When the beverage travelled north and south, the consumption style and the palate of people defined the beverage. As for the question of when and where was milk added to tea, historians believe that the first iteration of chai with milk was developed by travelers and traders, most likely from Gujarat, Maharashtra and Bengal, people who had easy access to good quality milk.

Even the weather influenced the taste of India’s primary beverage, says Rohak Sheth, co-founder and director, Tasse de Thé. In colder climes, heat-producing ginger and cardamom were added to tea. In Southern India, masala chai is not popular; instead, tea brewed with milk and sugar is the prime beverage. Popular tea brews in Assam are ronga sah, which is a red tea without milk, and gakhir sah, a milky tea. In North India, popular tea brews are masala chai, kadak chai, which is a very strongly brewed tea, almost bitter, and malai mar ke chai, which has a dollop of full fat cream.

Before the countrywide consumption of chai rose to popularity, Indian kitchens served their own version of herbal teas. Possibly using common Indian plants and spices such as holy basil (Tulsi), cardamom, pepper, liquorice (Mulethi), and mint.

Photo Courtesy: Mr. Flatlay / Pixabay

Today, luxury tea brands not only provide consumers with varieties to make their daily cup of masala chai, but also aid the revolution of green and white tea, that can be had without milk or sugar. Lifestyle change has played a massive role in this shift of tea preference wherein consumers have become more health-conscious and try to avoid milk tea. “As a tea lover and a tea sommelier, I believe tea is best consumed without milk for its complete health benefits and pure taste,” says Neha Mary, Tea Sommelier, The House of Tea by Foodhall, who herself prefers minimally processed white tea. Tea was deemed a medicinal plant in China when first discovered, and consumed by the monks. Only recently has that knowledge pervaded the world, thanks to the world wide web.

The evolution of tea took an interesting turn with the internet boom, which lead to greater awareness of other cultures. As Indians started to travel more than ever, it only furthered their experiences with different tea traditions. The Japanese conduct elaborate tea ceremonies, the British have tea rooms and all of these experiences influenced the consumption back home.

Jhawar also credits our changing global attitude, “We Indians have evolved quite a bit. We are more accepting of other cultures and traditions and that’s changed our lifestyles and habits, including tea drinking. People are just not buying regular green tea, they want it infused with turmeric or tulsi.”

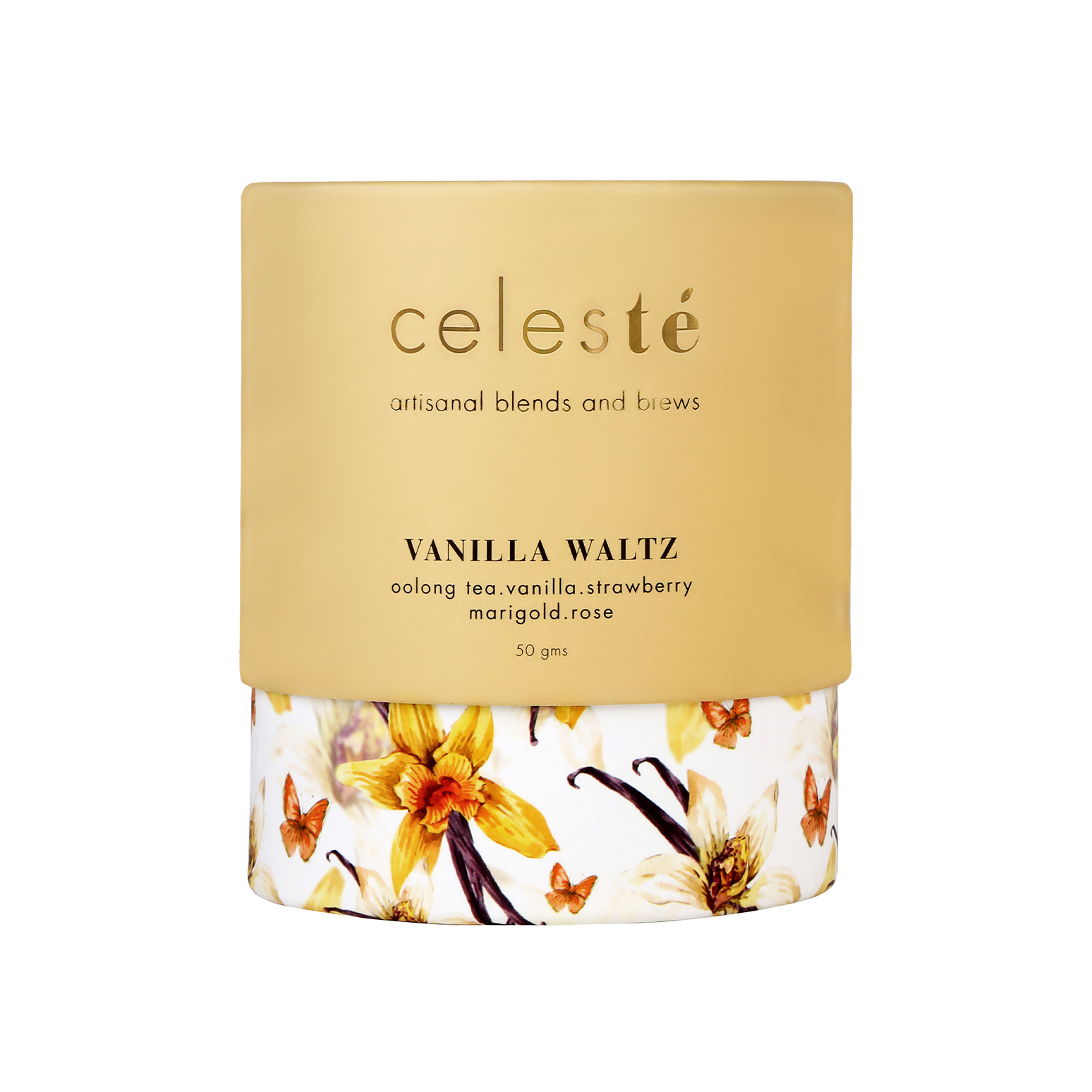

Celesté’s Vanilla Waltz Tea

At Tasse de Thé, Sheth mentions a rise in demand for matcha, a Japanese origin, finely ground powder of specially grown and processed green tea leaves. Sheth attributes this boom to the need for immunity-boosting products during the pandemic. Matcha is one of the strongest types of green tea, with lots of vitamins, fibre, and antioxidants.

Photo Courtesy: Pixabay / Pexels

However, the shift from granulated CTC tea to long leaf teas and green tea blends, involves a change in the brewing process. Jiten Sheth, co-founder and tea blender at Tasse de Thé, and India’s first tea blender, certified by the International Tea Master’s Association, stresses that India still needs to learn how to brew tea correctly.

Through education and awareness, India looks poised to accommodate more varieties of teas in the market. No matter your preference masala chai or jasmine green tea, both, happily co-exist in this land of contradictions and similarities.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.